Ground Facts and Truth #2

Follow-up to: On Ground Facts.

The Status Quo

At present, most information is relayed by news services that republish or piggyback the Associated Press or Reuters. In other words, they typically pick up and repackage the information gleaned from other primary news-sharing services (supplementing it with their own primary news and investigative journalism) and there's absolutely nothing wrong with that model per se.

Even still there are some decisive advantages to adopting a shared "fact ontology" in my opinion:

- Investigative journalism is limited by the expertise and knowledge of interviewers. If a person doesn't what a topic is, that a problem exists, how it is a problem, or somewhere to look for such a problem they will miss it. That's lost value from a journalism standpoint.

- Misinformation, fake news, and misreporting happen all the time even amongst those who take the profession quite seriously. Human mistakes happen.

Assuming a "ground-fact ontology" were to exist:

- The story-writing would still be original.

- Humans would submit contributions to the overall fact dataset. Humans would "discover facts" and submit them.

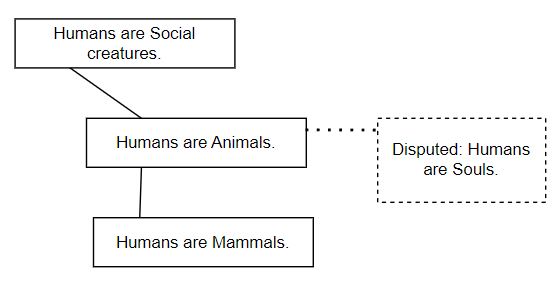

- People could dispute the facts (as I mentioned before - state representation - "the state of affairs" e.g. - the sum totality of all facts using philosophy-speak).

- Automated fact-checking would be enabled.

The Internet and online encyclopedias also serve as major sources of information and to relay facts, etc. Still there are some clear advantages to a "ground-fact ontology" when compared against those extant resources as well:

- Not HTML based.

- Online encyclopedias are awesome but have their obvious limitations. Many articles present a compressed version of the primary academic source texts and the quality of an article or topic depends deeply on the volunteers who dedicate their free time to what's basically the transcription of primary sources into various plaintext (or file) formats. Many articles I've read of interest lack footnotes, good summaries, and so on (history topics tend to be very thorough and lovingly documented but others not so much). It's not real-time - most articles are fairly out of date and only incidentally updated (due to someone volunteering to do so).

- Neither easily lend themselves to automated theorem proving (example: given ground fact

Humans are Animals and Mammals, thatAdam is a Human, a ground fact thatAll humans have a certain DNA feature X, an input DNA strand not containingX, and so on - one could deductively verify that:Adam is an Animal and has feature X in his DNA, thatthe input strand is not a human- just some very simple examples). - Both rely on human search and a myriad of indexed Internet resources.

- Both would benefit from an independent fact-checking system - that's one of the most notorious (and accurate) criticisms of the Internet and things found within it!

- Would be an implementation-neutral abstract data format that's amenable to common Automated Theorem Proving techniques and I think of great use when validating scientific theories, the accuracy of certain fact-claims, etc.

On Disputation

My opinion is that most disagreements about claims almost always drill down into a debate about Facts (e.g. - state representation - how we understand and present something in the world).

Definitions don't typically engender as much debate. Here's my argument why:

- Suppose you and I disagree about the meaning of some term

X, what's standard practice is to add to the definition ofXany accepted conventional meaning and these become Senses (in philosophy-speak). - Go to any online physical dictionary and you'll, of course, see the enumerated semantic meaning (each different semantic meaning is akin to what Frege called a Sense - a shade of semantic meaning or definition if we give it a descriptive gloss) - the multiple definitions of a term or word.

- Moreover, just go to a couple of different dictionaries and you'll see even more variations.

So, lexical disputes of that nature really then come down to:

- Which of these two conventional meanings is the accurate (factual) representation of the relevant concept at hand. E.g. - even if we continue to disagree on the term, it becomes a state representation about the appropriateness of a particular definition at that point.

- Otherwise, most thinkers will divide the prior question into two:

- Does my definition of

Xapply? - Does your definition of

Xapply? - We see that we're just talking past each other with different meanings. We are really discussing two distinct concepts:

X₁,X₂. - And, so in such a scenario the question just becomes two state representation questions.

- Does my definition of

Example: consider a disagreement about the term: "car". Suppose I believe cars must have four wheels, that the new compact tricycle electric cars can't be a "real car". And suppose you disagree with me.

We could debate the ultimate accuracy of that term (which would really be whose concept is the most accurate one?) or we could accept we have different definitions or shades of meaning and we'd add both definitions to the dictionary if they weren't there already. Something to the effect of: (1) a vehicle with 4 wheels (stringent), (2) any enclosed vehicle, etc.

Universal Fact Ontology for Knowledge Representation

To some extent, schooling attempts to create standards around knowledge (or standardized knowledge if you prefer). Wouldn't it be more helpful to present the sum totality of postulated human knowledge in a universal format?

Here's how I'd envision this:

- Knowledge is clustered and divided into regions.

- These regions can be described using handy labels (like

Sub-Region 42.1.3a). - Facts don't exist infallibly - they can be disputed and commonly held alternative views are considered to be part of the overall web. One cannot obtain a total understanding of a "region of thought" without being familiar with the most commonly held range of views.

- This approach encourages Skepticism and the ongoing process of tidying up human knowledge.

- It presents knowledge universally and in real time.

- Could be open-source and exist in primarily digital as well as physical format.

- Could be monetarily free and could supplement curriculums everywhere.

I'd foresee epochal knowledge events (such as the move to the Copernican Model, etc.) as being strongly encouraged and indeed celebrated. To "overturn" a cornerstone fact or region (replacing the "default", dominant, or primary position with a new one) would be one of the highest achievements an intellectual, thinker, scientist, etc. could strive for.

Clarifying My Criticism of Pyramid Metaphors

I've addressed this in a few places already but want to draw out the primary criticism from my past post on this topic:

- A metaphor that provides the skeleton and edifice for a view that also

- lends itself to a multiplicity of meanings and interpretations isn't a very satisfactory basis for a view.

This smacks of the imprecision in philosophical image-metaphor use I've discussed previously and it's easy to see why. If say Foundationalism appears coherent and compelling on the basis of a "levels (of a pyramid)" metaphor (some facts are fundamental and are the basis for the next "layer" of facts - that they ascendingly justify the next batch), that one can run the same geometric metaphor the other way should undermine that view.

- Remarks on Truth-Grounding and the Liar

- Remarks on Truth-Grounding and the Liar #2

- Ground Facts and Truth

- Ground Facts and Truth #2

- Addressing Metalogical Justification

- Propositional Stability and Cohen Forcing

- Truth as a Prosentential Operator

- The Liar Paradox in Programming

- Fun Math Stuff and the Philosopher's Stone

- Fun Math Stuff and the Philosopher's Stone #2

- Fun Math Stuff and the Philosopher's Stone #3

- Restrictionism and the Four Corners of Logic

post: 03/09/2024